Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, or DBT, is one of the few evidence-based therapies proven to be successful in treating those struggling with high levels of emotion disregulation. DBT not only provides the structure and skill-set to be able to work with clients with borderline personality disorder, but also has broader application in treating depression, PTSD, anxiety, eating disorders and substance abuse. Adherence to the DBT model is essential at achieving targeted outcomes and preventing therapist burn-out by using a team-based approach. Below is a brief overview of the structure of this highly effective modality.

DBT requires adherence and commitment.

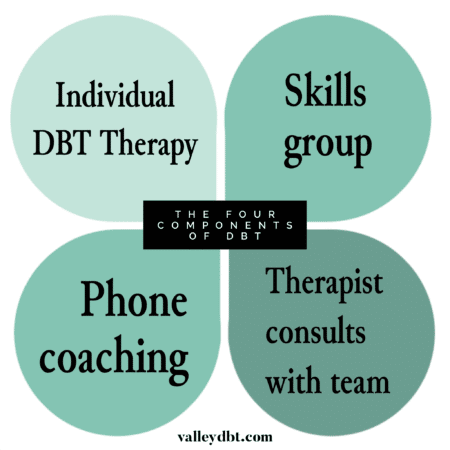

For a client to fully participate in a program – and to legitimately be called DBT – they must attend weekly individual DBT therapy, a weekly skills group, complete homework assignments, and have access to phone coaching with the therapist. (Some therapists have limited hours for phone calls, others are available around the clock, depending on personal limits.) The therapist must be part of a DBT team, a critical piece in preventing therapists from getting burnt-out and overwhelmed. Teen DBT adds weekly family skills therapy to the protocol.

Since these components add up to be quite a big commitment for both client and therapist, before starting, a certain amount of time is spent with the client in “pre-treatment.” This usually occurs over the course of 3-4 sessions where both client and therapist discuss therapeutic goals and determine if they can work together. The therapist makes no qualms about the difficulty of treatment and lets the client know that they will have to work very hard. The therapist may even discourage the client to commit to therapy unless the client is highly motivated (door-in-face technique) while balancing this with encouraging statements to entice the client to commit (foot-in-door). If the client still wants to continue with treatment by the end of pre-treatment, both client and therapist will sign a contract, usually for 6 months to 1 year in duration. (The contract maybe renewed again after completion.) This agreement becomes a focal point of leverage when the client wavers, engages in behavior that interferes with treatment, or wants to quit therapy.

The Development of DBT

In the 1980s Marsha Linehan discovered that CBT alone wasn’t working with highly suicidal clients because the treatment was too invalidating. After all, it takes a certain amount of ego-strength to admit things need to change. While most clients can handle this idea, for many clients, recognizing they may be ill-equipped to cope in certain areas of life feels unbearable. Or they may not have the skills to solve the problems that are creating their misery. Linehan recognized this and added validation and dialectical strategies. One of the first opportunities for validation when working with a borderline client may be in introducing the idea that clients may not have created all of the problems in their life, yet they have to deal with them anyway. The therapist might say, “This situation may not be your fault, but what are you going to do about it?”

DBT introduces the concept of a Life Worth Living, helping clients see beyond their immediate problems and work towards broader life goals. This helps to instill hope and working at the acquitision of behaviors that help clients achieve their life goals and reduce misery and despair.

Linehan also added mindfulness strategies to treatment after training for many years with a Zen master. She knew that clients often get so caught up in intense emotions that it takes them out of the moment, sometimes even skewing reality. Mindfulness became a cornerstone of treatment, teaching clients to stay present, and tolerate big feelings.

She also added a team-based approach, a necessity in keeping therapists from dropping out as well. After all, DBT can be tough work. Linehan describes working with borderline clients like working with a third degree burn victim. Their “emotional skin” is so incredibly thin that their lives are unbearable. This is why DBT treatment is like walking a tightrope. It’s a delicate dance of balancing opposing forces. The need for validation is carefully balanced with strategies to create change. In other words, it’s a dialectic.

What does ‘Dialectical’ mean?

Dialectic is a philosophical term to describe two opposing truths that exist at the same time. We see them in life all the time. One example is a love-hate relationship. We don’t always like the things friends and family do, in fact we can be really angry with them at times, yet we can hold loving feelings simultaneously. Many of our clients often have trouble holding dialectical points of view, which can lead to an all-or-nothing approach, and big problems in interpersonal relationships. DBT seeks to explore a dialectics, or a middle path, searching for a synthesis to black and white thinking. This corrects the tendency for thoughts and emotions to swing too far in any one direction, and practically speaking, helps prevent a lot of bridge burning in relationships. It brings the client back to a more mindful, centered, and effective approach to any given problem. Over time, the client learns to control intense emotions, which prevents vigilance and emotional reactivity.

Clients are encouraged to challenge the ‘myths’ of these black and white thoughts. For example, if a client subscribes to the idea that “showing emotions in a form of weakness,” the client would be asked to find an alternative perspective. The clients might discover that showing emotion can be helpful in letting others know we need help. Often times, when using this skill, a client will say, “Yes, but I don’t believe any of the challenges to the myth.” DBT says you don’t have to believe the challenge to the myth, you just have to be willing to find an alternative perspective.

Willingness

The concept of willingness is perhaps the most helpful part of DBT treatment. Often, the client’s participation in therapy, particularly when there is a lot of resistance, hinges around a discussion of willingness vs. willfulness. In DBT the therapist always refers back to the original treatment contract. The client was initially willing to come to therapy and willing to make the necessary changes to improve their lives. They must be reminded of this. For example, when a client is asked to practice or role-play a skill in session, they might say, “I just don’t feel like it today.” The therapist would remind the client that in order for therapy to work, they have to be a willing participant – something they agreed to early on. This highlights another dialectic. How does the therapist advocate for the client to move past their willfulness while respecting the client’s personal limits in the moment?

Reducing Fragilization

DBT subscribes to the belief that clients should not be treated as fragile, preventing the feeling of “walking on eggshells.” After all, clients need to deal with life on life’s terms, which isn’t always fair. Often times therapists will find themselves going out of their way not to upset the client. One of the roles of the DBT team is to point out when this might be happening, give the therapist feedback, and support the therapist to treat the client like anyone else. This might require a certain amount of bravery on the part of the therapist!

As an example, a therapist might be nervous to change the session time to attend a doctor’s appointment, fearing the client might get upset. However, the team might encourage the therapist to proceed anyway. After all, doctor’s appointments are part of life and something the client needs to deal with. If an upset does occur, this might even be an opportunity for the client to practice new skills.

It’s easy to see how a ceratin clients might be called ‘manipulative,’ shaping the behavior of those around them. This term is discouraged in DBT. All things being equal, the client is actually not being manipulative, but using what skills they have to make a situation work to their advantage. However, their ability to foresee consequences in relationships may by limited. DBT therapists take a non-judgmental approach with clients, leaving out the concept of a bad and good, and instead looking at consequences to behavior.

Individual Therapy vs. Skills Group – What’s the difference?

Clients in an adherent DBT program must attend both individual therapy AND skills group each week. While many clients may benefit from skills group, it must be disclosed to the client that this is not the comprehensive DBT protocol. At San Fernando Valley DBT clients with outside therapists may attend the skills group as long as this is clinically appropriate.

The DBT skills group itself is more like a class than a process group, where clients focus solely on learning the skills. The group covers four modules: Core mindfulness, Interpersonal effectiveness, Distress Tolerance, and Emotion Regulation. It takes approximately 6 months to complete the skills and then the course is repeated. The DBT skills can be conceptualized like learning a language; it takes time to become fluent and repetition is tantamount to using the skills in an effective way.

In individual DBT therapy, the therapist covers a structured protocol and sets an agenda for the session. There is a hierarchy of treatment, whereby self-harming behavior (such as cutting or drinking) is always addressed first. If no self-harming behavior has occurred, then behavior that interferes with therapy is addressed, then behavior that interferes with quality of life. Family history and trauma may be addressed if clients are able to tolerate exposure to these difficult emotions. In general, the goals of each session include problem solving, skills generalization, contingency management and emotion exposure.

While the structure and techniques of DBT may seem unconventional compared to other therapies, the framework gives the therapist leverage to work with highly reactive clients. The team approach ensures the therapist is well supported and limits burn-out and feelings of overwhelm. DBT is comprehensive approach and requires a commitment from both client and therapist, however once the commitment is made, DBT can be extremely exciting and rewarding work.